A Literal Bridge from the Future to the Past

Robin Roemer is a Strong Towns reader who lives in San Jose, California. He is the parent of a student at Orchard School, where the city has plans to widen an adjoining street from two lanes to four and build a new overpass to serve as a truck route across busy Interstate 880. Roemer has helped organize Orchard parents in opposition to this plan. Today, we are sharing a guest post he wrote about the situation.

Source: City of San Jose (click to view larger)

North San Jose, CA, in the San Francisco Bay Area, is currently undergoing rapid development. Much of it is designed along lines that Strong Towns speaks positively of: a place where you can work and live in close proximity. Plans for North San Jose emphasize dense housing, transit, complete streets and walkable neighborhoods. With 32,000 new residential units, 100,000 new jobs, and 26.7 million square feet of new industrial development by 2040, it is one of the larger urban experiments currently underway in this country.

But—and there always is a “but”, isn’t there?—zoom out just a little bit, and you will see many neighboring areas caught in a more car-centric past with big stroads and suburban style development.

As long as these two approaches are physically separated, there is little immediate conflict.

However, as the City of San Jose is currently trying to design a new bridge over the I-880 freeway that runs between the “Urban Villages” of North San Jose and the more suburban areas to the freeway's east, the disconnect between these two approaches becomes obvious.

Lush Bicycle-Focused Parkway vs. 7-Lane Trucking Route

Left: North San Jose framed by Guadalupe River (left) and Coyote Creek (right). Right: San Jose suburbs. (Click to view larger)

On the western side of the planned bridge, and part of the area covered under the city's North San Jose Development Policy, is Charcot Avenue. According to the North San Jose Urban Design Guidelines, this will be transformed in to a “Parkway,” a street that

“has a more lush, vegetated character created through a combination of planted medians, generous landscaping along their street and building edges, and two lanes of traffic moving at relatively slow speeds.”

The General Plan calls for Charcot Avenue to include an “On-Street Primary Bicycle Facility,” giving priority to bicyclists over cars.

But on the eastern side of the overpass, and outside of the North San Jose master plan, the bridge will turn into a four-lane wide, car-centric road and connect to Oakland Road, an existing 7-lane stroad and major trucking route through San Jose.

A City Plan Stuck in the Past

Current design plan for the Overpass, school with ballfield to the right. Classrooms bordering the new road in the middle of the picture. (Source: City of San Jose. Click to view larger.)

The city argues that since the project has been planned since 1994 [see page 6 of linked document], it needs to primarily follow what was codified in the City’s General Plan back then. The proposed overpass's main purpose, according to these priorities, should be to create more space for more cars to move more freely through the area. "Freely" being relative, as traffic studies by the city have shown that the overpass is expected to almost immediately become just congested as the neighboring streets which cross over 880.

The city does plan to throw in some bike lanes and sidewalks too, but they are so much of an afterthought that they aren’t even included in many of the regional bike plans.

Building the Charcot overpass to carry up to 1000 cars and trucks per hour is especially concerning because this new street will be built directly next to a public K-8 school. Or to be more precise, on top of what are now parts of the school’s baseball field and the elementary school playground.

Given the school’s already unfortunate proximity to a major highway (I-880) and a major trucking route (Oakland Road), the further deterioration of air quality that can be expected adds to our worries.

Left: Orchard School. Middle: Silk Wood Lane, the future east end of the overpass—the current plan calls for four lanes here. Right: Residential neighborhood, with a large mobile home park further right (outside of the frame). Almost 300 students live on this side of the school. (Click to view larger)

It will put an additional barrier between the school and the homes of about 300 children living on the other side of the future road. This will make it less attractive to walk to school and more dangerous. The project is very likely incompatible with the City’s commitment to Vision Zero, a pledge to end all traffic deaths.

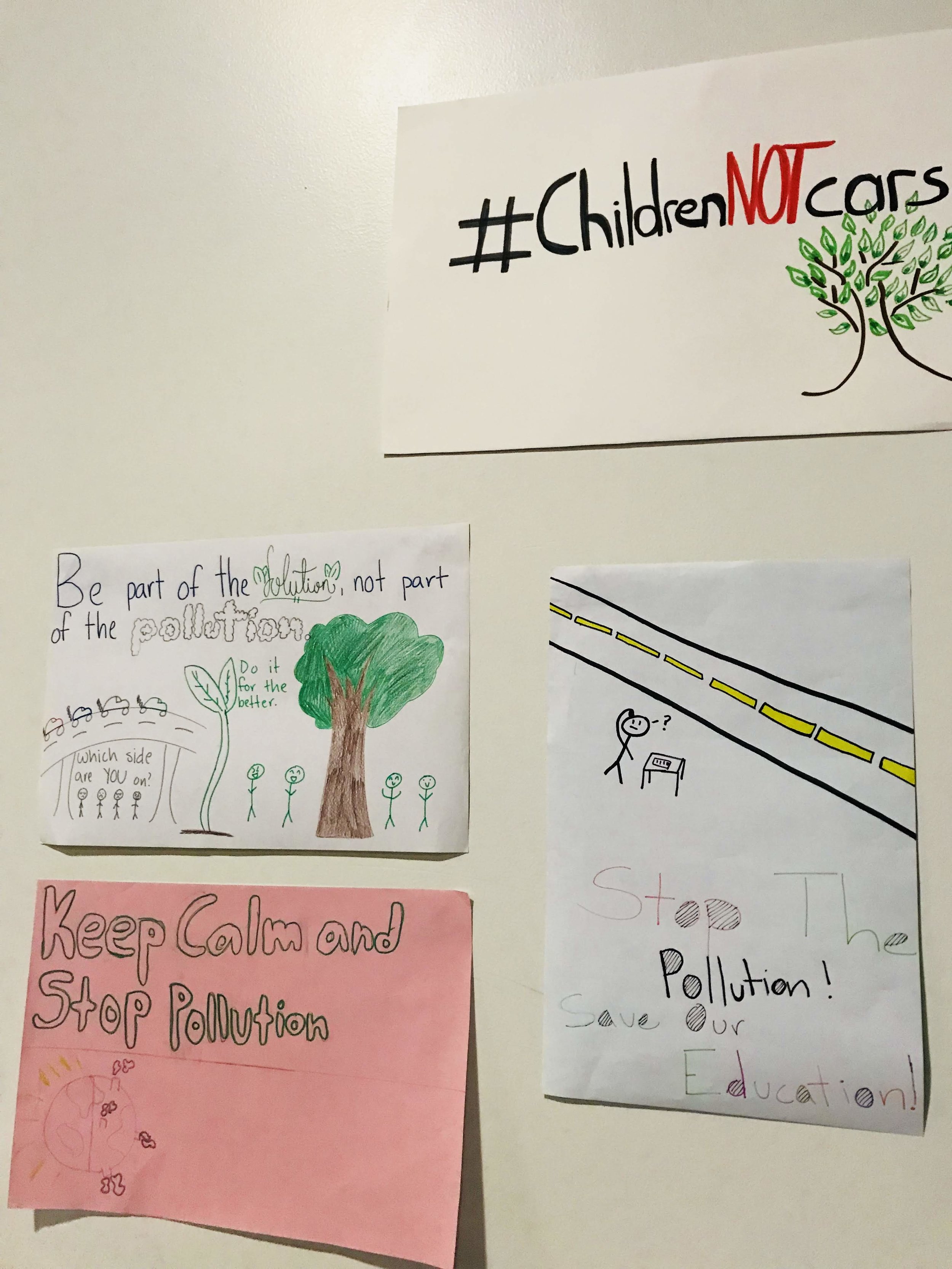

We parents at the school believe building the overpass in its current form is a horrible idea and one that only keeps the city stuck in its car-centric past. We will continue to fight for a safer, more forward-thinking solution during the City’s current effort to update other parts of the North San Jose Development Policy, as well as during the overpass’s environmental review process. A draft EIR (Environmental Impact Review) is expected in January; the final EIR will then go to the Planning Commission, and finally to the City Council.

A Bridge Into the Future

To look for a stronger, more suitable and sustainable solution, one doesn’t need to look far: just to the opposite, western end of this same project. If bikes and pedestrians will be prioritized on Charcot Ave, why not extend that to the bridge, and create a bike- and pedestrian-only overpass from the Orchard school area into North San Jose?

This would discourage people from driving into North San Jose, contributing to a more walkable and livable environment there. It also would encourage people to move closer to North San Jose in order to be able to walk, bike or use transit to work, creating additional pressure to build out the area as a complete neighborhood, with housing closer to this employment center. It will help the City achieve its goals of increasing trips by walking or biking ten-fold by 2040 and having single drivers make up fewer than 12% of commuters by 2050.

And our children at our school would be better protected from car crashes and pollution as well.

Why Hasn’t the City Changed its Plan?

Is it the inertia of lines on paper?

Maybe.

Here is what we hear:

From the engineers: The plan calls for a road, so we will build a road.

From the planners: We can’t just change one piece of the plan; we need to keep it consistent. Our traffic studies say we need a road.

From the politicians: The people currently stuck in traffic demand more roads.

So for now, the project remains unchanged, because there has been no champion for change within the city—only the 850 children at our school.

About the Author

Robin Roemer is the parent of a first grader at Orchard School. Originally from Germany, he has been living with his family in North San Jose since 2010. To find out more about the parent protest against the overpass project, go to https://orchardpta.wixsite.com/orchardpta/charcot-protest.